I’m a big fan of disruption. It’s an acquired taste. But because virtually everything is being disrupted these days, from groceries to government, it’s something we should learn to appreciate.

We often cheer disruption from a safe distance because overturning established institutions is in the American DNA. Most of us like to think of ourselves as rebels (unless we’re taking about the Confederate kind). But when we’re invested in the institution being overturned, our first impulse is to dig in our heels.

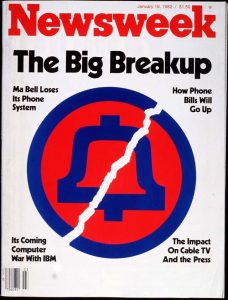

I was immersed in disruption for much of my career. I worked for the telephone company from 1968 to 1990 and had a front-row seat for the breakup of AT&T, at that time the largest corporate reorganization in history. It was a great experience, though I did not always think so at the time.

I was immersed in disruption for much of my career. I worked for the telephone company from 1968 to 1990 and had a front-row seat for the breakup of AT&T, at that time the largest corporate reorganization in history. It was a great experience, though I did not always think so at the time.

The Bell System was a well-managed monopoly with a century-long tradition of excellent telephone service, a close-knit corporate culture and nearly a million loyal employees. It was disrupted by advancing technology, changing markets and shifting consumer sentiment — culminating in an antitrust suit in 1974 that broke up the company a decade later. The phone company had done nothing wrong, but the things we did well were no longer as important to our customers as the promise of wider choice and cheaper long-distance calls.

Our initial response was to circle the wagons because everyone’s identity was rooted in the Bell System’s stability and security. It was hard for us to believe that customers liked their telephone service but still favored breaking up the company. We were convinced that telephone service was going to fall apart.

Once change was inevitable we learned to cope with uncertainty and massive reorganization. It was messy at times, with management missteps and downsizing, but telephone service did not fall apart and neither did we. If the antitrust judge had changed his decision a decade later and told us to go back to being a monopoly, he would not have had many takers.

This sort of upheaval has been going on throughout American history. If competition is the engine of our economy, disruption is its turbocharger. Companies are routinely disrupted by innovation and competitive pressure, and successful companies disrupt themselves. We’ve seen Apple disrupt music and telecommunications. Video streaming services are displacing television and cable networks. Amazon disrupted publishing and is quickly taking over retail markets. Retail jobs are disappearing but distribution centers are hiring.

Disruptive renewal is harder for institutions that are insulated from the economy. Universities have been sheltered from market forces because they are either state-owned or government-subsidized. But declining enrollment, online competition, soaring costs and political unrest make higher education ripe for disruption. Can we get Amazon to buy a university?

The latest target of disruption is government itself. Donald Trump’s election was a hostile takeover of a government that had lost the trust of at least half the country. Unlike past changes of administration that left a permanent governing class untouched, this election repudiated a bipartisan set of assumptions and values to an extent we have not seen in more than a century.

It’s natural for bureaucrats, politicians and interest groups who were invested in the status quo to feel the same sense of existential threat I saw among telephone company managers in 1984. Historians recorded similar outrage after the presidential election of 1860.

Unlike a corporate takeover, government disruption can be reversed in the next election. This gives opponents incentive and opportunity to continue the fight and that’s what we’re seeing. Because Americans still identify with rebellion, it’s a smart tactic for the Democrats to brand their campaign to restore the old order as a Les Miz resistance movement.

Business disruptions take place when consumers embrace new ways to meet their needs and shop at Amazon instead of Sears. Whether this holds true for government remains to be seen. All we know right now is that the disruption and drama is not going to end any time soon and we’d better get used to it. The good news is that we get to vote on the outcome.

Lessons in disruption

I’m a big fan of disruption. It’s an acquired taste. But because virtually everything is being disrupted these days, from groceries to government, it’s something we should learn to appreciate.

We often cheer disruption from a safe distance because overturning established institutions is in the American DNA. Most of us like to think of ourselves as rebels (unless we’re taking about the Confederate kind). But when we’re invested in the institution being overturned, our first impulse is to dig in our heels.

The Bell System was a well-managed monopoly with a century-long tradition of excellent telephone service, a close-knit corporate culture and nearly a million loyal employees. It was disrupted by advancing technology, changing markets and shifting consumer sentiment — culminating in an antitrust suit in 1974 that broke up the company a decade later. The phone company had done nothing wrong, but the things we did well were no longer as important to our customers as the promise of wider choice and cheaper long-distance calls.

Our initial response was to circle the wagons because everyone’s identity was rooted in the Bell System’s stability and security. It was hard for us to believe that customers liked their telephone service but still favored breaking up the company. We were convinced that telephone service was going to fall apart.

Once change was inevitable we learned to cope with uncertainty and massive reorganization. It was messy at times, with management missteps and downsizing, but telephone service did not fall apart and neither did we. If the antitrust judge had changed his decision a decade later and told us to go back to being a monopoly, he would not have had many takers.

This sort of upheaval has been going on throughout American history. If competition is the engine of our economy, disruption is its turbocharger. Companies are routinely disrupted by innovation and competitive pressure, and successful companies disrupt themselves. We’ve seen Apple disrupt music and telecommunications. Video streaming services are displacing television and cable networks. Amazon disrupted publishing and is quickly taking over retail markets. Retail jobs are disappearing but distribution centers are hiring.

Disruptive renewal is harder for institutions that are insulated from the economy. Universities have been sheltered from market forces because they are either state-owned or government-subsidized. But declining enrollment, online competition, soaring costs and political unrest make higher education ripe for disruption. Can we get Amazon to buy a university?

The latest target of disruption is government itself. Donald Trump’s election was a hostile takeover of a government that had lost the trust of at least half the country. Unlike past changes of administration that left a permanent governing class untouched, this election repudiated a bipartisan set of assumptions and values to an extent we have not seen in more than a century.

It’s natural for bureaucrats, politicians and interest groups who were invested in the status quo to feel the same sense of existential threat I saw among telephone company managers in 1984. Historians recorded similar outrage after the presidential election of 1860.

Unlike a corporate takeover, government disruption can be reversed in the next election. This gives opponents incentive and opportunity to continue the fight and that’s what we’re seeing. Because Americans still identify with rebellion, it’s a smart tactic for the Democrats to brand their campaign to restore the old order as a Les Miz resistance movement.

Business disruptions take place when consumers embrace new ways to meet their needs and shop at Amazon instead of Sears. Whether this holds true for government remains to be seen. All we know right now is that the disruption and drama is not going to end any time soon and we’d better get used to it. The good news is that we get to vote on the outcome.

Share this: