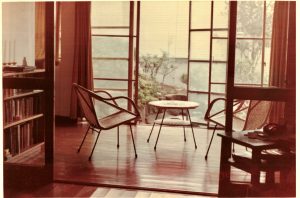

We had a picturesque apartment on the lower floor of a house on a steep hillside, half cave and half treehouse. A step down from the entrance hall to the living room, two steps down to a kitchen with windows on two sides, a step up to a bedroom with no windows. It was a romantic adventure (or so we kept telling ourselves): starting married life in an exotic country 6,000 miles away from both sets of parents.

I was at a joint-forces base in Albuquerque when the Navy finally ordered me to sea duty: a minesweeper homeported in Sasebo, Japan. “Sasebo’s a nice town,” said the Air Force colonel I worked for. “I bombed it once.”

Kathy and I had been dating and decided to get married before I shipped out so the Navy would send her to Japan, too. One of the many ways in which I was lucky in marriage was that Kathy was an Army brat who had moved a couple of dozen times. To her, an overseas move was business as usual.

I flew to Japan 12 days after we got married and Kathy joined me three months later, getting from Fukuoka to Sasebo by train on her own after a snafu in the Navy’s transportation arrangements. I was at sea when she arrived. When I returned the Navy housing office helped us find an apartment in town because base housing was limited.

Sasebo had recovered from the colonel’s World War II bombing when we arrived in 1966 and was a bustling seaport city. House-hunting was an adventure because an address identified a neighborhood of twisting streets and alleys and house numbers were sort of random. The cabdriver would stop in the center of the neighborhood and ask for directions from a couple of local guys who drew a map in the dust after a lengthy discussion.

Our neighborhood would drive a zoning inspector to drink: houses of assorted sizes shoehorned in wherever they would fit, crowding narrow streets with no sidewalks and an open-sewer “benjo ditch.” Because street parking was impossible, we had to rent an off-street parking space in order to license our car. Coming home entailed walking about a block uphill from the parking lot, descending a long staircase, walking along a footpath and down another flight of stairs to our front door. Carrying groceries was great exercise.

The Navy housing office provided worn but serviceable furniture and appliances. Kathy figured our refrigerator had gone through the war on the Japanese side. The apartment had two half-baths: a toilet and cold-water sink off the entrance hall, and a sink and bathtub off the kitchen. Hot water came from an on-demand water heater over the kitchen sink that lit a gas burner and shot out a tongue of flame toward your face when the faucet was turned on.

Sasebo’s winters are mild but our house was lightly built with no central heating. We dressed warmly and huddled around the space heater as the wind whistled up through the floorboards. Mildew was a problem in the topical summers.

Then there was the wildlife: gangly spiders the size of a saucer. Kathy emptied a can of bug spray on one before we learned they were non-poisonous and easy to dispatch with a flyswatter. There also were centipedes. One Navy wife photographed the exotic insects in her house and mailed the photos to her husband at sea.

Sasebo was less westernized than Tokyo and some people still wore traditional Japanese dress. Getting around was an eventful ride through Kamikaze traffic and the occasional street market. Japanese drive on the left side of the street (most of the time). Our VW Beetle was a medium-sized car by Japanese standards but still was a tight fit for the narrow streets. We were told there had been few motor vehicles in Sasebo until recent years, and it looked like everyone was learning how to drive together. The two-way street near our house was wide enough for one car and Japanese drivers were sensitive about losing face.

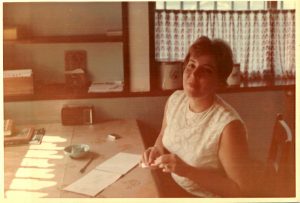

The mechanics of living in Sasebo kept Kathy busy while I was at sea for a couple of months at a time. She drove down to the base every day to pick up mail. My letters took a couple of weeks to reach her via a supply ship, an aircraft carrier in the Tonkin Gulf and the Philippines. Daily visits to the exchange store and commissary were necessary because when a scarce commodity (such as hair spray) appeared on the shelves it was snapped up quickly.

Most Navy families hired Japanese help: At a couple of dollars a day you couldn’t afford not to. Families with children complained that their Japanese nannies spoiled the kids rotten. Our cleaning lady, who came once a week to clean and do laundry, spoke no English and Kathy’s Japanese was limited. When the plumbing froze one winter morning Kathy found the cleaning lady outside the house, trying to thaw the water pipe with burning newspaper. She pointed to the pipe and explained “mizu (water).” Kathy pointed to a pipe a few inches away and asked what it was. When the lady replied “gasu,” Kathy emphatically convinced her that the burning newspaper was a bad idea.

Our elderly landlord and landlady, whom we nicknamed Mama-san and Papa-san, lived upstairs. Mama-san apparently believed that if she chattered enough Japanese at us we would eventually understand her. Paying the rent once a month was a mini-ceremony in Japanese etiquette. I’d greet them, exchange bows, and give them the money. Then they would bow and I would bow in response. And then they’d bow again. Since I was usually in uniform, I would straighten up after a few rounds of bows and salute. This caught them off balance and allowed me to get out the door before they bowed again.

We never got to know our Japanese neighbors. When I went out in the morning I often saw some of the neighbor men urinating in the roadside ditch. Who would greet me with a bow, of course.

Fortunately, we had American neighbors. Our enterprising landlord had built two small houses on his property to rent to Americans. We also attended the occasional social function at the officers’ club, though Kathy found the wives’ club scene boring and took a Japanese flower-arranging class instead.

Our favorite hangout was a joint known as a stand-bar, where the hostesses served drinks and flirted from behind the bar instead of cuddling in booths for drinks. Kathy was popular with the hostesses, who had learned all their English from talking with drunken sailors. They fussed over her when she became pregnant: “No mo’ drink fo’ you — baby-san get stinko.” We explored the local restaurants and learned not to ask what was in the food.

Our adventure came to an end in typical Navy fashion when I came home one day and announced: “We’re leaving Japan a week from Sunday.” “Where?” Kathy replied. “Great Lakes, near Chicago.” “Sounds good.” She was four months pregnant at that point and did not relish having a baby (and a Japanese nanny) in Sasebo. We’d had enough of Japan and Kathy was starting to understand Mama-san.